- Appreciating the Whale Diet Culture Anew

Takeo Koizumi

Professor of Tokyo University of Agriculture

Chairman of Group to Preserve Whale Dietary Culture - Ulsan and Whales

Che-Ik Lee

Chief of Ward Namgu / Ulsan Metropolitan City - Outline of the 2nd Traditional Whaling Summit

Shigeo Nakazono

Curator / Ikitsuki-cho Municipal Museum "Shima no Yakata" - Recent Activities of NAMMCO

Grete Hovelsrud-Broda

General Secretary to NAMMCO

ISANA Dec. 2003 No.28

index

ISANA Dec. 2003 No.28

Appreciating the Whale Diet Culture Anew

--Greeting from the new Chairman of the Group to Preserve Whale Dietary Culture--

Professor of Tokyo University of Agriculture

Chairman of Group to Preserve Whale Dietary Culture

I have the honor to assume the post of the Chairman of the Group to Preserve Whale Dietary Culture, succeeding Mr. Shotaro Akiyama who passed away in January this year. I am teaching food culture studies at Tokyo University of Agriculture. As Japan is an island country surrounded by the seas, it has seen the development of a unique fish dietary culture that has not been seen in any other parts of the world. The Japanese are rice-cultivating people, but more than that, they are fish-eating people. Here fish include the whale, and we are proud of being the people who historically loved and cherished the whale most of all nations. In any period of our history, we have revered and paid gratitude to the whale and have been strengthened by the benefit of valuable protein provided by the whale. The evidence that Japan cared about whales more than any anti-whaling country in the International Whaling Commission (IWC) can be witnessed in the fact that temples and shrines have been built near whaling ports in various parts of Japan as a token of respect and gratitude to the whale. It is no exaggeration to say that the blood of the whale has flown in each Japanese person who has consumed whale as important gift from the sea.

This whale culture, especially the whale dietary culture, which is filled with tradition, is now facing the risk of being driven to extinction by illogical sophistry of anti-whaling countries. This is sheerly an unacceptable situation. To date, Japan has been carrying out cautious scientific research on whales under the IWC Scientific Committee, and conclusions have been drawn that the continuation of the whaling culture in Japan can be fully guaranteed. However, anti-whaling groups try not to recognize these findings.

As I was appointed the head of the Group to Preserve Whale Dietary Culture, I am committed to appeal our reasonable position not only overseas but also widely among the Japanese people. I call it an offensive drive in defense of whaling dietary culture. I am thinking of mobilizing the mass media and targeting women and children to gain understanding and cooperation for promoting the cause of maintaining our whaling culture. I am considering promoting the education of young people on the importance of whale dietary culture through educational programs at elementary and middle school levels.

On the occasion of assuming the chairmanship of the Group, I would like to introduce the full text of my article carried in the "My Viewpoint" column of the July 17 issue of the Yomiuri Newspaper.

It is indispensable to appreciate whale dietary culture

The original intent of the establishment of the International Whaling Commission was to research the whale resources scientifically to ensure proper utilization of the resources, to select the whales species that can be harvested and to determine catch quotas. For this purpose, the IWC commissioned its Scientific Committee to carry out scientific research. Over a long span of time, the Scientific Committee has conducted highly accurate research and analysis of the whale resources, and finally came up with a management procedure that can ensure utilization while allowing the resources to increase. The Committee recommended annual quotas to the Commission.

However, despite the progress in scientific research, anti-whaling countries, such as the United States, France and Australia, strengthened their political move behind the scene, and attempted to divert the original purpose of the scientific activities, ramming through the adoption of a commercial whaling moratorium. Since then, confrontation between whaling and anti-whaling members emerged, as repeatedly observed in the IWC annual meetings.

At the latest annual meeting in Berlin this past June, the whaling countries' request for the resumption of commercial whaling was refused by a seemingly violent exercise of unilateral forces by the anti-whaling bloc. On top of that, a resolution designed to turn the IWC into an anti-whaling organization was adopted. In other words, the original objective of the IWC to ensure "proper conservation of whale stocks and thus make possible the orderly development of the whaling industry" (preamble to the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling) was transformed into "conservation of whales" alone. Furthermore, the anti-whaling forces strengthened their protective stance by establishing the "Conservation Committee" to expedite their protectionist programs.

Thus, the anti-whaling countries acted recklessly to radically change the nature of the IWC. Their only reason is the "protection of whales." What we see there is a unilateral denial of science, without any theoretical backing. One cannot but feel futility when considering the continuous research and studies of the Scientific Committee's efforts so far.

Whaling nations, Japan being one, have their own traditional whale cultures and surrounding dietary cultures. Do the anti-whaling nations really have the right or the authority to drive that culture into extinction with the power of numbers? The anti-whaling countries blatantly disregard the basic objectives of the Convention advocating both the conservation and utilization of whale resources and deny lending their ears to the position of whaling nations. We should not overlook here that among the anti-whaling countries that voted affirmatively at the Berlin meeting for establishment of the Conservation Committee (versus 20 against), there are countries that have had no whale culture. Is this a true form of democracy? It seems to me that it is nothing but a kind of fascism.

It is shown scientifically that there exist about 760,000 minke whales in the Antarctic, and if those stocks are properly managed and conserved, commercial harvesting can be fully guaranteed, with no negative effect on their conservation. This conclusion of scientific research was totally disregarded by the outlandish tyranny of the majority.

It is a curious fact that the United States, which stands at the forefront of the anti-whaling campaign, is itself a whaling country. The U.S. government allows its Alaskan indigenous people to catch a 5-year quota of 280 bowhead whales under the name of subsistence whaling. Scientific surveys show that the bowhead whale is the most endangered species. It is this species that should be protected.

If whales are indispensable as food for native Americans, then the use of Antarctic minke whales, guaranteed as exploitable as a result of scientific research, is more compatible with "proper utilization and orderly whaling."

Some scientific surveys show that cetaceans consume fish in the amount of 3-7 times the human consumption annually, and the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and other fisheries management bodies warn against excessive protection of whales. If we leave the whales to increase simply because they are lovable animals, the marine ecosystem may be doomed to change. In order to cope with global food shortage, anticipated to occur not in the too long distance, the Japanese people should fully recognize the importance of whaling for the supply of food.

"Mr.Koizumi addressing upon assuming chairmanship of the Group to Preserve Whale Dietary Culture

Ulsan and Whales

Chief of Ward Namgu

Ulsan Metropolitan City

To begin with, I would like to express my gratitude for allowing me valuable space in "Isana," an opinion bulletin on whales. I would like to ask for your generosity in reading the amateurish writing of an administrative official who has no special knowledge on whales.

I. World's cultural heritage

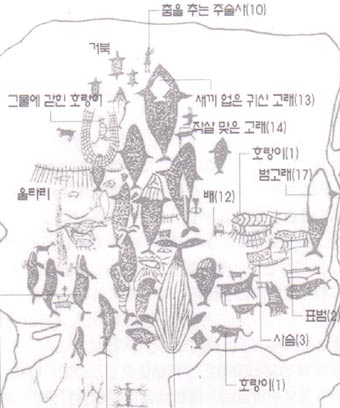

The name Ulsan immediately calls to the mind of the Koreans the image of whales. The relationship between Ulsan and whales dates back to pre-historic times more than 4,000 years ago. In the drawings engraved in the rock at Bangudae, designated as the National Treasure No. 285, we can see animals such as tigers that lived in many numbers in that period, but most attractive among them are undoubtedly the schools of whales--which number as many as 60 in the drawings.

What surprises us most after seeing the rock engravings at Bangudae is the large number of drawings of whales. These drawings are based on precise and objective observations of whale behavior. We cannot help but admiring the fact that all of more than 10 species of whales migrating in the sea near Ulsan were drawn.

The shape of a whale's blow differs from species to species. It is said that fin whales that spout in the V-like form of a fountain were often sighted in the waters near Ulsan's coast. Humpback whales that have unique wrinkles on the belly are expressed with several long lines on the body. Killer whales with a clear black-and-white contrast are also engraved faithfully to their markings. Especially the right whales truly resemble their actual figure with emphasis on the shape of the mouth. Also, a gray whale swimming with a calf on its back is realistic. The drawings also include sperm and other species.

Our ancestors who left the rock engravings are said to have had remarkable technical and cultural power in the pre-historic period. Whales, once harvested, were distributed in accordance with the structure and social status within the community. Bangudae rock engravings have drawings suggesting such a practice.

Unfortunately, the history of Ulsan, the Korean peninsula and a part of the world are now immersed in the water.

What I mean to say is that the rock engravings of Bangudae in Ulsan are under water except for three to four months in the winter during the dry season. Furthermore, the engravings face the danger of wearing off, with their surfaces damaged severely by weathering of more than 4,000 years. Also repeated exposure to the air for three to four months every year accelerates the wearing because of congelation and melting water.

Reproduction of the Bangudae petroglyphs

The water which washes the rocks creeps into the crevices, further expanding them, and when the water withdraws, rocks have fissures by reduction of the pressure and dehydration. When you compare the present rock engravings with the replica manufactured in the 1970s, you will find conspicuous damage on the rocks and wearing down of the engravings, which present a really miserable sight.

At present, many scholars are engaged in studies on how to preserve these valuable remains. As one who is in charge of Ulsan's civil administration and as a politician, I feel myself responsible for the Bangudae rock engravings being left in this status. As a measure to preserve them, I think Bangudae should be registered as a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage. I would like to take this opportunity for support and assistance to all the people of the world concerned with whales.

II. Ulsan and Whales

The history of whaling in Jang-seng-po in Ulsan began in the late 19th century when Pacific Whaling Co. of Russia discovered large schools of whales off this town, and leased the area near the port of Jang-seng-po as a whaling base with the aim to harvest whales by obtaining the whaling right from the Korean government.

Later, Japan came to monopolize the whaling business after its victory in the Russo-Japan war. Jang-seng-po in Ulsan became the center of whaling from around 1915.

When Korea became independent from Japan after World War II, the whaling company, thus far managed by the Japanese, re-started as Chosun Whaling Co., fully invested by Koreans.

The first whale, a killer whale, was caught on April 16, 1946 by a whaling boat transformed from a wooden fishing boat. In 1966, the wooden whaling boats were replaced by steel vessels. There are records that those vessels caught an annual average of 700 whales (cf. History of Whaling in the Sea Near the Korean Peninsula by Koo-Byong Park). The town so thrived by whaling in the 1970s that one saying goes even a dog carried a 1000-won bill (now worth about ?1000) in its mouth in Jang-seng-po.

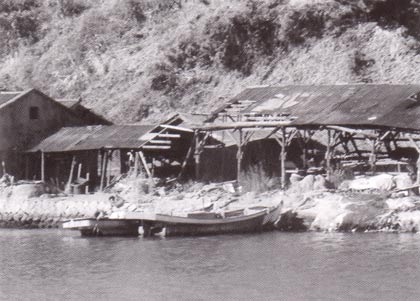

However, since the enforcement of a commercial whaling moratorium, only two decayed whaling vessels and a deserted whale flensing station was left in Jang-seng-po, once the forefront of Korean whaling, rendering the town a desolate place.

Reproduction of the Bangudae petroglyphs

As I am not a whale biologist, I cannot accurately tell the number of whales living in the waters near Ulsan at this moment, but I receive reports that the number of whales has largely increased since 1986. (According to data by National Fisheries Research & Development Institute, the number of whales reported to have been taken incidentally in fisheries or stranded in the seas surrounding the Korean Peninsula in 2002 was 280 from 12 different species. )

I am convinced that the day will certainly come when whales are landed in Jang-seng-po, although I am not sure what types of harvesting will take place, be it research whaling or whaling for the purpose of management.

As chief of Ward Nambu of Ulsan Metropolitan City, I have a scheme to revive Jang-seng-po (which once thrived by whaling) as a new town through such efforts as construction of a whale museum, restoration of the whale flensing station, invitation of the Cetacean Research Division of National Fisheries Research & Development Institute to the town, and improvement of hygiene at the whaling station (at present many of the incidentally caught whales are processed in an unsanitary manner in the whole area of the eastern coast E Pohang, Yeongdeok, Hupo, Samcheok, etc.

I believe such a scheme will certainly serve for the benefit of Jang-seng-po and also for the future whaling in Korea.

Reproduction of the Bangudae petroglyphs

Outline of the 2nd Traditional Whaling Summit

Introduction

The 2nd Traditional Whaling Summit was held in Ikitsuki-cho on May 11, 2003. The event was organized by the Ikitsuki Municipal Office in collaboration with the Institute of Cetacean Research (ICR) and the Japan Whaling Association (JWA). With the cooperation of many townspeople, including the Women's Group, participants in the main meeting during the afternoon of May 11 exceeded 700. The study session and the symposium were also successful. Above all, I would like to extend here my heartfelt gratitude to many representatives of whaling-related local autonomies from all over Japan and scholars who travelled all the way to our town located on the western tip of Japan. Although there is a lot to be reported, I would like to summarize only the salient aspects of the event because of the limited space allowed to me.

1. Whale-related folk art

On the eve of the event, May 10, a festival was held at the Seamen's Welfare Hall in Tachiura, in which whale folk art in Nagasaki Prefecture was introduced: Ejima whale songs from Ejima in Sakido-cho and Arikawa whale songs from Arikawa Town in the Gotoh Islands. The latter especially has so far been presented in various parts of Japan. This time as well their songs and dances were performed excellently. The former has been unknown among whale folk art researchers, and came to light when local people presented a report several years ago. No performance outside the prefecture has taken place so far, so, in this sense, the presentation provided a good opportunity to both performers and audience.

On the other hand, the summit meeting was started with whaling songs by an Ikitsuki folk art preservation group. During the intermission, middle school students presented their whale song performance. Lavish applause was given to this gallant song performed with 10 drums by students clothed in gorgeous "happi" coats marking the flags of a big harvest.

2. Whale cuisine

In the pre-summit festival, a variety of whale foods was presented by representatives of whale-related local autonomies all over Japan. The reproduction of traditional cuisines and original cooking was also presented under the guidance of Mr. Ayao Okumura. Especially, the whale sukiyaki which Mr. Okumura reproduced on the basis of "Kujira-chomi-kata," a whale cooking manual compiled in the Edo Period by Masutomi-gumi in Ikitsuki, and whale iriyaki, a traditional cuisine of Ikitsuki, provided a comparison between old and present whale sukiyaki. At lunch time on May 11, whale with rice, whale soup and fried whale meat were offered for free to the visitors in the plaza in front of the hall. The food prepared for 2,500 persons quickly ran out. Members of cooking schools and a women's club in Tachiura volunteered for the preparation of the food. They said the participation in the event was very enlightening for them in learning how to cook whale.

3. Sightseeing tour

In the morning of the summit day, a sightseeing tour was organized to historical remains related to whaling in the northern part of Hirado Island. A total of 170 people, largely exceeding the number we had anticipated, took part in the tour. It was a happy surprise for me who served as a guide in the tour. But honestly it was laborious work requiring extensive care. During the tour, I introduced the gun-based whaling in Seto, Hirado, and the net-and-dart whaling in Ikitsuki Island, with a special emphasis on the relationship between whaling grounds and whaling methods taking into consideration the contents of an academic presentation scheduled for the afternoon.

4. Study session and the symposium

It was very significant that the origin of whaling in Japan was confirmed by the participants under the major theme of primitive and ancient whaling. To begin, the present author reported about local whaling in the Hirado Islands region. Mr. Koo-Byong Park, Emeritus Professor of Pukyong National University, then made a presentation on the rock drawings of whales and whaling in Bangudae in Ulsan. Mr. Issei Kanada, a member of the Education Board of Kumamoto City, pointed out the possibility that whaling in ancient times had taken the form of positive rather than passive harvesting, because the earthenware using whale bones as bottom plates, which had been distributed in Kyushu in the middle of the Jomon Period, showed that the bones had been those of large whales, and the plates themselves decayed as time passed. Mr. Susumu Tatehira, Professor of Nagasaki International University, presented an overview of whale bones used as products and tools as well as drawings of whaling, each from the Jomon Period, Yayoi Period and Old Grave Period. He suggested the possible presence of whaling, including more passive harvesting, and also considered the use of whale-attracting techniques which are used frequently nowadays.

The symposium was coordinated by Mr. Masayuki Komatsu, Director of the Resources and Environment Research Division of the Fisheries Agency. Mr. Tetsuo Hiraguchi, Professor of Kanazawa Medical University, lectured about whaling culture in Northern Japan, especially in the Okhotsk Sea region in Hokkaido, including a presentation on the Mawaki archeological remains. This was followed by reports on the instance of primitive and ancient whaling in Iki Island by Mr. Jungo Shiraishi, curator of Iki Local Culture Museum, and by Mr. Katsuaki Morita, Professor of Konan Women’s University, on modern whaling in the Korean Peninsula from the perspective of interchanges between Japan and Korea.

In the general discussion, participants exchanged views on the issue of the origin of Japanese and Korean whaling and the propagation of whaling practices. It was also pointed out that there existed a common whaling culture in the whaling grounds around Tsushima Strait that transcended the national borders that came to be introduced in later years.

At the symposium it was confirmed that the use of whales began in the Japanese archipelago about 9,000 years ago, and there is a possibility that the harvesting of large whales took place about 2,000 years ago.

On the basis of what was discussed, the Ikitsuki Declaration calling for the need to sustain the Japanese whaling culture having such a long tradition was adopted and the whole event was concluded.

Performance of Ejima whale songs

Symposium

Recent Activities of NAMMCO

General Secretary to NAMMCO

NAMMCO - the North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission - is an international body for co-operation on conservation, management and study of marine mammals in the North Atlantic. The NAMMCO Agreement focuses on contemporary approaches to the study of the marine ecosystem as a whole, and to understanding better the role of marine mammals in this system. Through regional co-operation, the member countries of NAMMCO aim to strengthen and further develop effective conservation and management measures for marine mammals. Such measures are based on the best available scientific evidence, and taking into account both the complexity and vulnerability of the marine ecosystem, and the rights and needs of coastal communities to make a sustainable living from what the sea can provide. NAMMCO provides a mechanism for co-operation on conservation and management for all species of cetaceans (whales) and pinnipeds (seals and walruses) in the region, many of which have not before been covered by such an international agreement.

The Agreement to establish NAMMCO was signed in 1992 by the current members of the Commission - the Faroe Islands, Greenland, Iceland and Norway. NAMMCO had its beginnings in earlier international conferences on marine mammals, first held in Reykjavik in 1988 and also attended by Canada, Japan and Russia. At the 1990 meeting of the conference in TromsE a memorandum of understanding was signed by the four Nordic North Atlantic countries to establish an informal North Atlantic Committee for Co-operation on Research on Marine Mammals (NAC). The Parties to NAC agreed to work towards the development of mechanisms to ensure the conservation and management of marine mammals. From this process evolved NAMMCO.

The recent activities of NAMMCO include new abundance estimates for a number of North Atlantic whale stocks based on the North Atlantic Sighting Surveys conducted in 2001. These international surveys, which began in 1987, have provided a unique source of information on the distribution, abundance and trends in abundance of several whale stocks, including fin, minke, pilot, sei, northern bottlenose and blue whales. This information is crucially important in the management of whale stocks, and also in the assessment of their role in the ecosystem.

One desired objective identified in the NAMMCO Agreement is the ecosystem approach to management of living marine resources, placing NAMMCO at the forefront of efforts to implement such approach. Based on the on-going work of the NAMMCO Scientific Committee on marine mammal - fisheries interactions a broad-based approach is needed to identify the changes in management systems that might be required when using a multispecies, ecosystem-based approach. As a result a new Working Group on Enhancing Ecosystem-based Management has been established this year under the Management Committee. This Working Group will consider recent developments in this area, identify the challenges faced in adapting management systems to ecosystem-based approaches, and recommend what kinds of principles and measures can be applied. In addition the Working Group will investigate the progress that has been made in other fora in implementing such an approach.

Under the Scientific Committee a series of Working Groups have been considering pertinent scientific questions on marine mammal - fisheries interactions. In the early stages one Working Group considered bio-economic models of varying complexity and ecosystems, but with no conclusive results due to lack of data. At its 8th meeting, in 1998, the NAMMCO Council tasked the Scientific Committee with providing advice on the economic aspects of marine mammal-fisheries interactions, with a particular focus on the harp and hooded seals and minke whales, the species of economic interest to some of the NAMMCO member countries. A Working Group on the Economic Aspects of Marine Mammal - Fisheries Interactions met in 2000 to consider parts of the request. One of the conclusions of the Working Group was that significant uncertainties remain in the calculation of consumption by marine mammals, and this uncertainty was the most important factor hindering the development of models linking consumption with fishery economics (NAMMCO 2001). Considering this conclusion, the Scientific Committee decided to convene a workshop to further investigate the methodological and analytical problems in estimating consumption by marine mammals. This workshop, held in 2001, resulted in, among other things, a list of research priorities to refine existing estimates of consumption by North Atlantic marine mammals (NAMMCO 2001). The list included a focus on distribution of prey species in place and time, spatial and temporal distribution of the diet composition of harp and hooded seals and of minke whales in areas where such information is lacking, and the diet composition of the white-sided, white beaked and bottlenose dolphins.

The NAMMCO Scientific Committee viewed the next logical step in this process to be a review of how presently available ecosystem models can be adapted in order to increase our understanding of and quantifying marine mammal - fisheries interactions. A Workshop held in 2002 was tasked with choosing a preferred modelling approach for analysing the ecological role of minke whales, harp and hooded seals, and other marine mammal species in the North Atlantic, identifying required input data, and recommending a process for further development. The Working Group considered descriptions of the range of available multispecies modelling tools. This include two general classes of models typified by the Minimum Realistic Models (MRM) on the one hand and the ECOSIM/ECOPATH approach on the other. The MRM class includes MULTISPEC, BORMICON/GADGET and Scenario Barents Sea. These models share the characteristics of being system specific, modelling only a small component of the ecosystem for a specific purpose, and treating lower trophic levels and primary production as constant or varying stochastically. In contrast, ECOPATH/ECOSIM is an all-inclusive approach that incorporates lower trophic levels and primary production. Mass balance equations are used, essentially relating production by some species to predation by others under the assumption that the system is in a steady-state. ECOSIM builds upon this approach, but drops the equilibrium assumption so that the system is modelled by a set of coupled differential equations. Potentially ECOSIM, like the MRM class of models, could provide a basis to provide advice on marine mammal-fisheries interactions. Considering the data available or likely to become available in the foreseeable future, the Working Group favoured the Minimum Realistic-type model, as exemplified by Scenario Barents Sea, MULTSPEC and BORMICON approach of using a limited model that encompassed only the major species of interest, as opposed to an all-encompassing model where all or most species are included, as a basis for potential management advice in the short to medium term (NAMMCO 2002).

In reviewing the amount of multispecies modelling work and associated applications to management decisions that had been conducted world-wide over the past several years, the Working Group noted a much lower than expected activity in this area. This was considered surprising given the emphasis politicians and management authorities have placed on multispecies (ecosystem) approaches to the management of marine resources. While the principle of multispecies management seems to be widely accepted, the practical aspects of putting it into practice lag far behind the rhetoric. Progress in this area will not be made unless significant additional resources are dedicated to it. Finally the discussion of the economic aspects of marine mammal-fisheries interactions would be premature until at least one of the Minimum Realistic Models have been developed. Once models are available that can predict the variation in target species in response to management measures, linkages to simple economic models that assess the economic consequences of the responses can be made (NAMMCO 2002). The next steps forward will include a focus on assessing modelling results from Minimum Realistic Models, and to consider the feasibility of connecting the multispecies models with simple economic models.¥

References

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission, 2001.

NAMMCO Annual Report 2001. North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission, TromsE Norway, 335 pp.

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission 2002

NAMMCO Annual Report 2002. North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission, TromsE Norway, 357 pp.